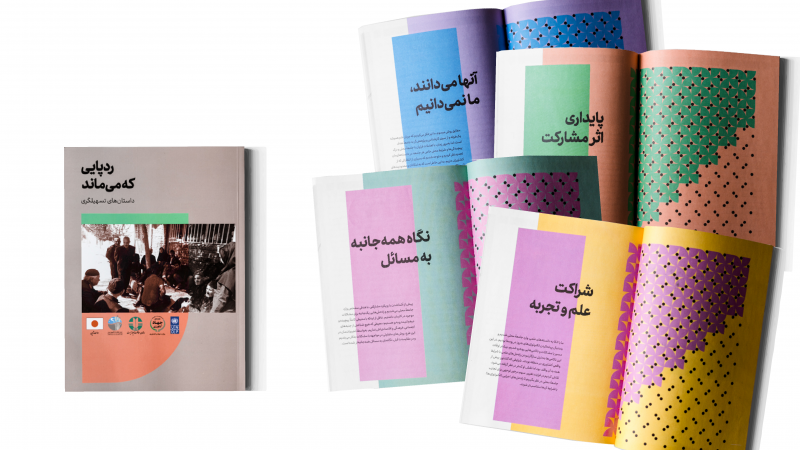

A review of the book "Traces that remain"

In one of the educational workshops[1] of the institute, to review the workshop activities, one of the participants volunteered to read parts of the book "The Trace That Remains" and find the connection between this book and the concepts and exercises of the workshop and share it with other participants. put Mr. Verjavand[2] had communicated well with the stories of the book and made a presentation related to the concepts of the workshop from this book. For this reason, we requested him to write his review of this book, so that we can share it with other interested parties on the institute's website. In the following, you can read Mr. Verjavand's note about this book.

[1] Training workshop "Getting to know the concept and principles of cooperative work"

Perhaps the most important feature of this book is the change of the authors' point of view, as you will see by reading each experience. At the beginning of entering the local community, the author had the paradigm of things [1] in mind; But seeing the characteristics of the local reality, i.e. the variety of problems, their complexity, the unpredictability of variables and dynamics in the audience, he realized that it is not possible to interact with the paradigm of things and it is necessary to believe in the ability of the local community to manage and solve problems.

In all the stories of the book, rejection of this thinking and change of attitude can be seen. The first principle of collaborative work [2] that is imprinted in the mind by reading the book is the principle of "Be quiet and listen". This principle actually expresses the farmer-first paradigm [3] (in local agricultural communities), which is rooted in the change in the view of the role of the farmer in third generation agricultural societies [4] compared to industrial agriculture (first type) and green revolution agriculture (type II) has In addition to this important principle, in the different stories of this book, traces of the principles of collaborative work can be seen in interaction with local communities. The most prominent of these learnings are the principle of "abandoning what has been learned" in the story, "The closures have not yet been reached", the principle of "do it yourself" (find the clues in the story), the principle of "respecting differences" (in the story when I recognized their privacy), the principle of "in the arms of Catching mistakes" (in the story the wind took my treasure, not my will), the principle is "they can handle it" (in the story of water in the jug and…). Reading the book, in addition to showing the important principles of the collaborative approach, narrates real and concrete examples that can be a guide for people who experience this process for the first time.

This book is a collection of real experiences about how to communicate with local communities in order to achieve common goals. These experiences are expressed by facilitators who once believed in educating local communities, not accompanying them. These experiences will tell how the attitude of people or external institutions to the ability and knowledge of these communities will change and how they will accompany local communities to recognize, analyze and solve their problems. By reading the book, the reader will find that many existing assumptions about the lack of awareness and the low level of knowledge of native people are not only wrong, but contrary to expectations, these communities will have the ability to solve their problems in the best way. In this regard, it can be said that the facilitator provides a platform where, in a society with different opinions and to some extent conflict of interests, different opinions of people are heard so that common and suitable solutions can be extracted from these opinions. Facilitators can help farmers to first analyze their situation and available resources, then plan a set of actions and implement, monitor and evaluate them.

When talking about education and promotion, the general premise is that of the university classes, where a person with the grandeur of a professor is at the head of affairs and determines the path of thinking, analysis and conclusions of a number of students and, following that, according to a certain intellectual standard And the top-down view guides the class and completes it in a certain period of time. This teaching method has been accepted in undergraduate and graduate courses and in university systems; But by studying the experiences of the authors, we can see that the farmer in the societies with third-generation agriculture should be looked at like a doctoral student who, unlike the previous two stages, the university system as an external institution, does not look at him as an uninformed person, and the professor The figure of a friend and colleague will accompany the doctoral student to solve a scientific problem (the subject of the doctoral thesis), without looking up and down in this relationship. This change of view in the university system, to the doctoral student compared to the students with lower degrees, is to continue to prove the ability of this person after passing various tests and classes. In the third type of agriculture, unlike industrial agriculture and the green revolution, the local community has been able to deal with various natural and human problems for generations without having full access to facilities and technology, such as a doctoral student who, by passing various tests and classes, has improved his ability to Every external entity asserts and needs to be heard and trusted in solving its own problems. In this book, the farmer's farm is in the form of a research environment, the farmer is in the form of the center of innovation, and the promoter and expert is the friend and companion of the farmer, not a professor from outside.

One of the steps in implementing collaborative projects is how facilitators enter local communities, which plays an important role in the project process and may affect future projects in that community. This book can be a pathfinder based on concrete and simple experience, in order to enter local communities as a facilitator. By reading the book, the principles of using a participatory approach will be clarified for the reader, and while advancing in the facilitation process, useful experiences about dealing with the third type of agricultural society will also be shared.

[3] Keshavarzakhest is the literal translation of the phrase farmer-first, which Chambers uses as an umbrella.

He invented the cooperative approach in the field of agriculture. In this approach, the priorities and participation of farmers play a fundamental role; It means that the participation of farmers should be developed and adapted in the place where farmers live. This phrase is explained in detail in the fifth chapter of the book "Challenge with Professions".